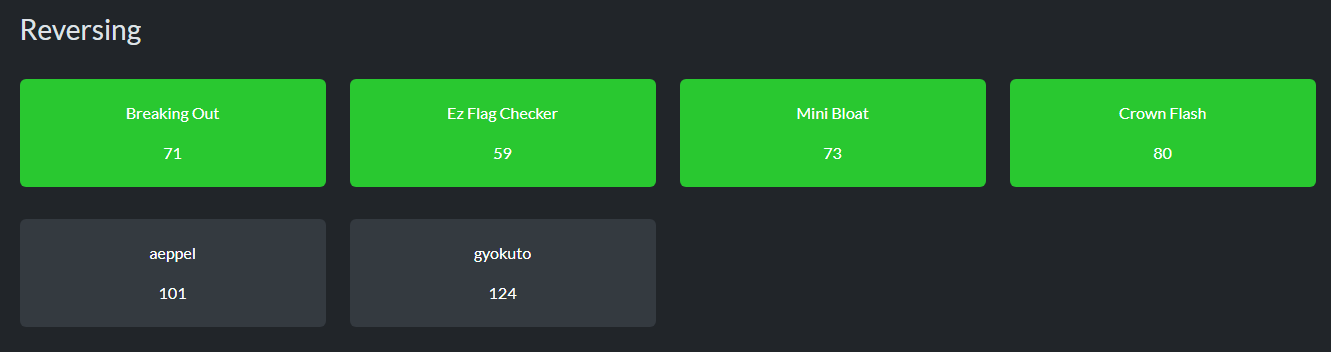

Reversing#

Crown Flash#

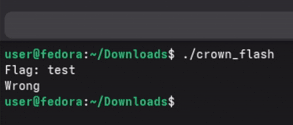

Context & initial static pivot#

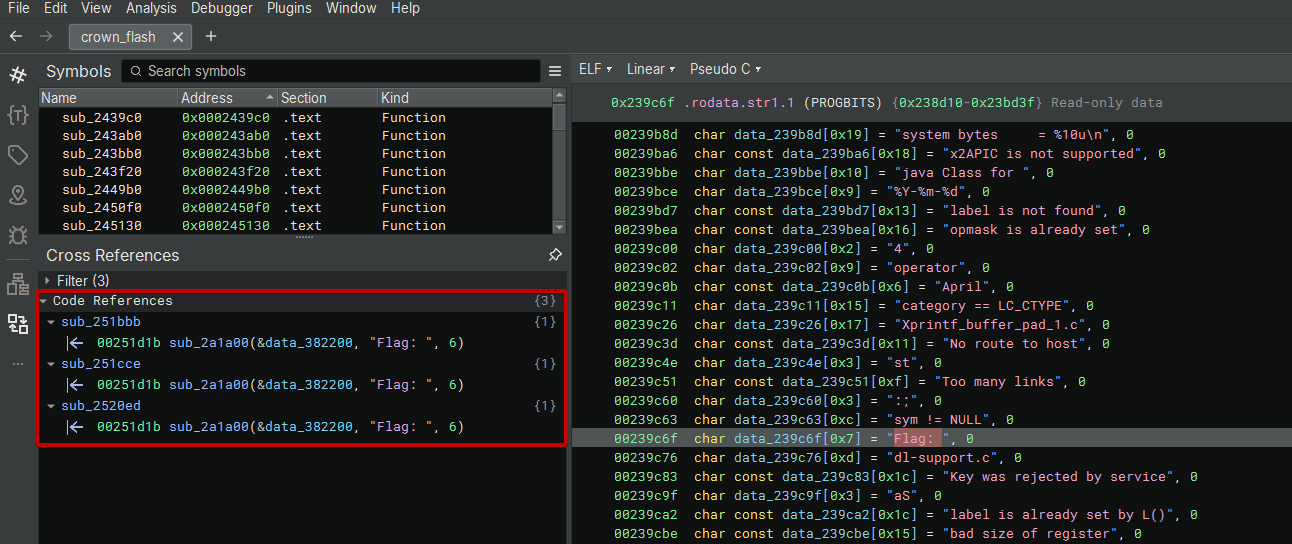

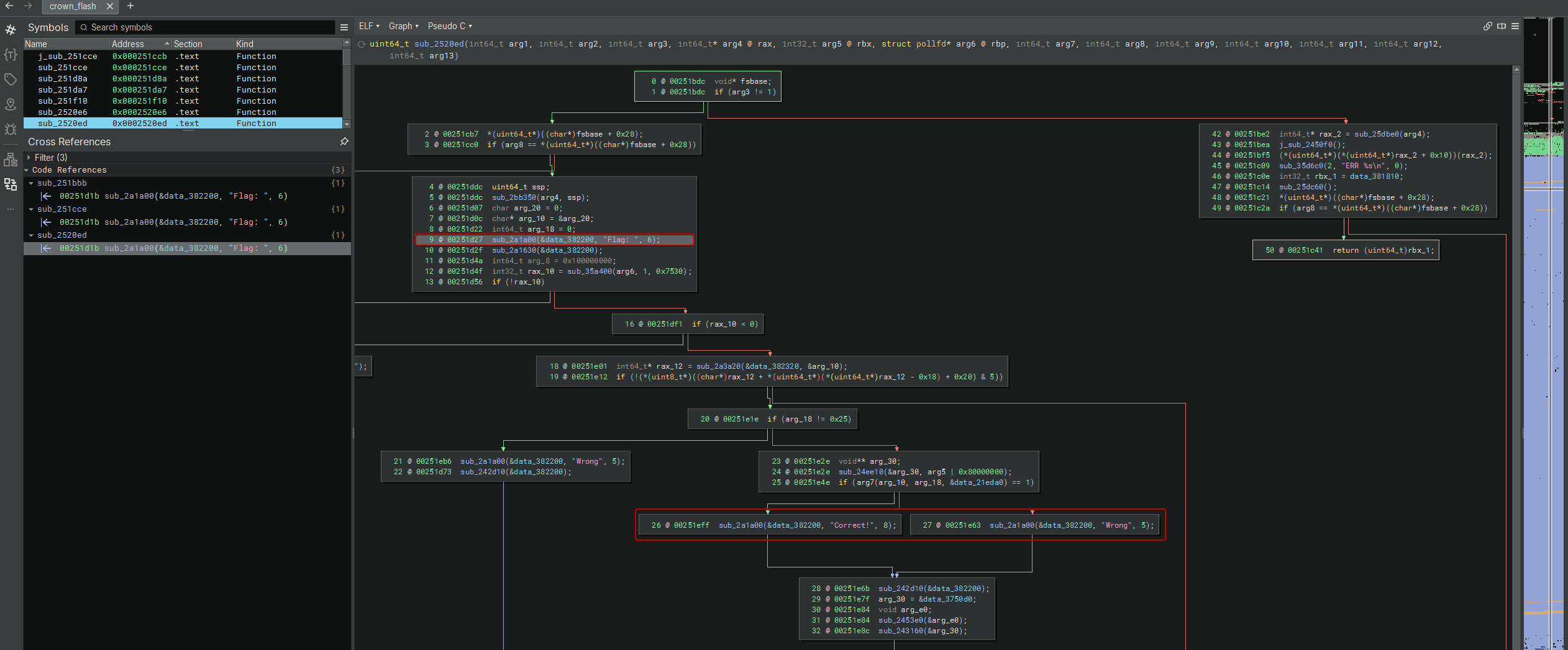

I’m trying to get more familiar with Binary Ninja so I used it for this challenge. The quickest anchor is the user-facing prompt string, so I searched for “Flag:” and followed its code references:

One of the references leads to the main interaction routine:

At a high level, this routine:

- prints

Flag: - waits for input (with a timeout)

- reads a line into a buffer

- enforces an exact length check (

0x25bytes) - calls a validator through an indirect function pointer (critical pivot)

- prints

Correct!orWrong

The binary asks for an input (“Flag: …”) and returns Wrong if validation fails. The interesting part is: the validation logic is not fully present in the main .text in an easy-to-follow way. Instead, it eventually does an indirect call into a memory area that looks like:

- not part of the main ELF’s

.text - not part of libc

- typically a anonymous executable mapping (often RWX in CTF packers/JIT-style stubs)

This is a common CTF anti-static pattern: hide the real validator until runtime, then jump to it.

Goal: recover the validator and its associated constants, then rebuild a solver.

Dissecting the “routine” wrapper#

Binary Ninja shows the routine as sub_251cce(...) with a lot of “mysterious” arguments because it’s inside a larger C++ program and BN is reconstructing a non-trivial calling context. The portion that matters for reversing is the I/O + dispatch logic:

- Stack canary / SSP noise (ignore, but recognize it) We see patterns like:

- reads from

fsbase + 0x28 - compares at function exit

- calls a noreturn abort-like function on mismatch (

sub_35da60)

That’s the standard x86_64 stack protector canary. It’s not part of the challenge logic, but it is useful to recognize so we don’t spend time on it.

- Prompt + timeout:

poll(..., 0x7530)The routine printsFlag:and then calls:

sub_35a400(arg4, 1, 0x7530)0x7530 = 30000ms (30 seconds).

Then:

- if return == 0 -> prints

Too slow! - if return < 0 -> errors out (

poll) - else -> proceeds to read input

This is a typical anti-bruteforce/anti-automation measure, but more importantly it tells that the binary is checking stdin readiness via poll() rather than just blocking on read(). That’s why “syscall-first” debugging is effective:

- Input is read through C++ iostream (why the decompile looks “weird”)

The visible routine does not directly

read(0, buf, ...)in a clean way. It goes through libstdc++ iostreams, then later materializes exactly what the validator needs: a(ptr, len)pair.

That’s why the decompiler shows pointer arithmetic such as:

*(rax + *(*rax - 0x18) + 0x20)

This pattern is typical of optimized C++ object layout:

raxis an iostream-related object (thinkstd::istream/std::basic_iosinternals),- the

*(*rax - 0x18)-style term behaves like a runtime offset used to reach a base-subobject/state area (common with virtual inheritance + Itanium C++ ABI), - the final

+ 0x20lands on a field that behaves like a stream state bitmask.

Semantically, the code is checking whether input succeeded using an iostate mask:

badbit = 0x1,eofbit = 0x2,failbit = 0x4(libstdc++-style layout)- testing

& 0x5means “reject ifbadbitorfailbitis set” - only if the masked result is zero does the routine proceed to validation.

Practical takeaway: we don’t need to fully reverse iostream internals. The register snapshot at the call site proves the actual validator ABI:

rdi = input_ptr, rsi = length, rdx = constants_table.

- The exact length gate:

arg_18 != 0x25

After the stream-state check, the routine enforces:

if (arg_18 != 0x25) -> "Wrong"

This is the first hard constraint we can reliably infer: the flag length is exactly 37 bytes.

A practical implication: when we later reconstruct the validator, our solver should iterate exactly 37 steps and treat the candidate as raw bytes (not necessarily null-terminated).

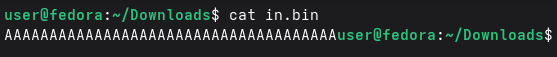

For now, I’ll create a in.bin with 37 A (without \n):

- The real pivot: the validator is an indirect call

Once length matches, the routine does:

sub_24ee10(&arg_30, arg3)(setup / context)if (arg6(arg_10, arg_18, &data_21eda0) == 1) -> "Correct!" else "Wrong"

This line is the whole challenge:

ok = validator(input_ptr, input_len, table_ptr);

where:

input_ptrisarg_10input_lenisarg_18(must be0x25)table_ptris&data_21eda0(the constant table used per index)validatoris arg6, not a fixed symbol, but a function pointer resolved at runtime

This matches our earlier observation of an indirect call *... and establishes the validator signature without needing to fully understand every C++ wrapper call

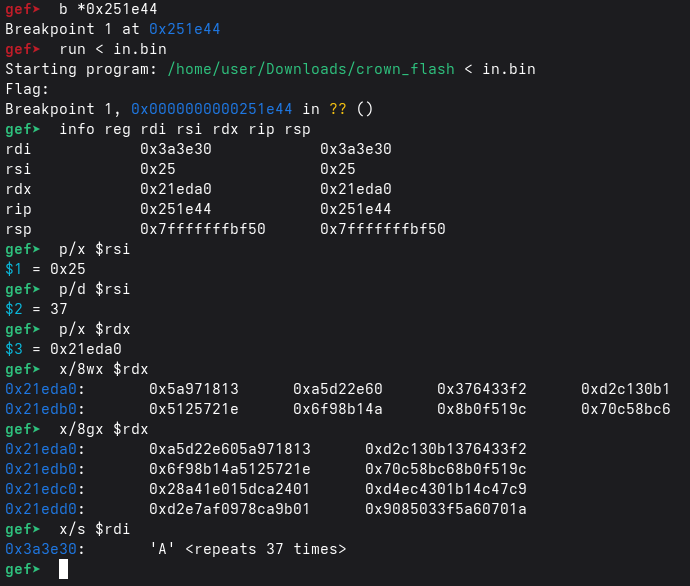

Finding input capture#

To find where the candidate flag is read we start by catching read and inspecting registers using the Linux x86_64 ABI:

For read(fd, buf, count):

rdi = fdrsi = bufrdx = count

At the catchpoint:

- inspect

rsito see what was read (x/s $rsiorx/32bx $rsi) - inspect

rdxto see the maximum expected size - use

btto locate where the program continues after the read

This establishes:

- the input buffer address

- the expected length (or at least the read limit)

- the control-flow path into validation

Identifying the pivot#

Following the backtrace into the main code reveals a key sequence that looks like:

mov ... , %rdi ; input pointer

mov ... , %rsi ; length

lea ... , %rdx ; pointer to a constant table

call *0xc8(%rsp) ; indirect call through stack-stored pointer

At the call site, the program performs call QWORD PTR [rsp+0xc8], i.e., the validator entrypoint is not a static symbol but a pointer stored on the stack. Dumping that slot (x/gx $rsp+0xc8) reveals the concrete jump target 0x7ffff7ff6000.

Sanity check: the indirect call target (*(void**)($rsp+0xc8)) falls inside the rwxp anonymous mapping, so we’re not guessing, we’re literally jumping into runtime-generated code.

Disassembling that address (x/8i $tgt) shows valid function prologue instructions (pushes and constant initialization), confirming it is executable code. Finally, /proc/<pid>/maps shows 0x7ffff7ff6000-0x7ffff7ff7000 rwxp … 00:00 0, meaning an anonymous RWX page (not backed by the ELF or libc), which is a strong indicator of runtime-generated/unpacked code.

Seeing an anonymous RWX mapping (rwxp + file 00:00 0) is not “normal program behavior” on modern Linux:

- Why RWX matters: it means the page is both writable and executable, so the process can generate or decrypt code at runtime and immediately run it. This is a classic pattern for unpacking / JIT / staged validators.

- Threat model intuition: the binary is deliberately structured so that the “real logic” is absent from .text and only exists in memory, defeating purely static reversing (strings, xrefs, naive decompile).

- Reverse-engineering consequence: the workflow shifts from “find a function in the ELF” to:

- capture the function pointer (here: the indirect

call *0xc8(%rsp)target), - confirm the page is executable (

info proc mappings//proc/<pid>/maps), - dump the page (

dump memory/dump binary memory) and analyze the generated code directly.

- capture the function pointer (here: the indirect

- Security aside: systems enforcing strict W^X policies typically avoid RWX; CTF binaries often keep it RWX for simplicity, but the concept is the same as real-world loaders (write -> mprotect RX -> execute).

Important observations:

Indirect call (

call *0xc8(%rsp))

This is the hallmark: the target is not a fixed symbol, it’s a pointer computed/loaded at runtime.Registers line up with a classic validator signature:

rdipoints at the input string/bufferrsiis the input length (here: 37,0x25)rdxpoints at a table of constants used during validation

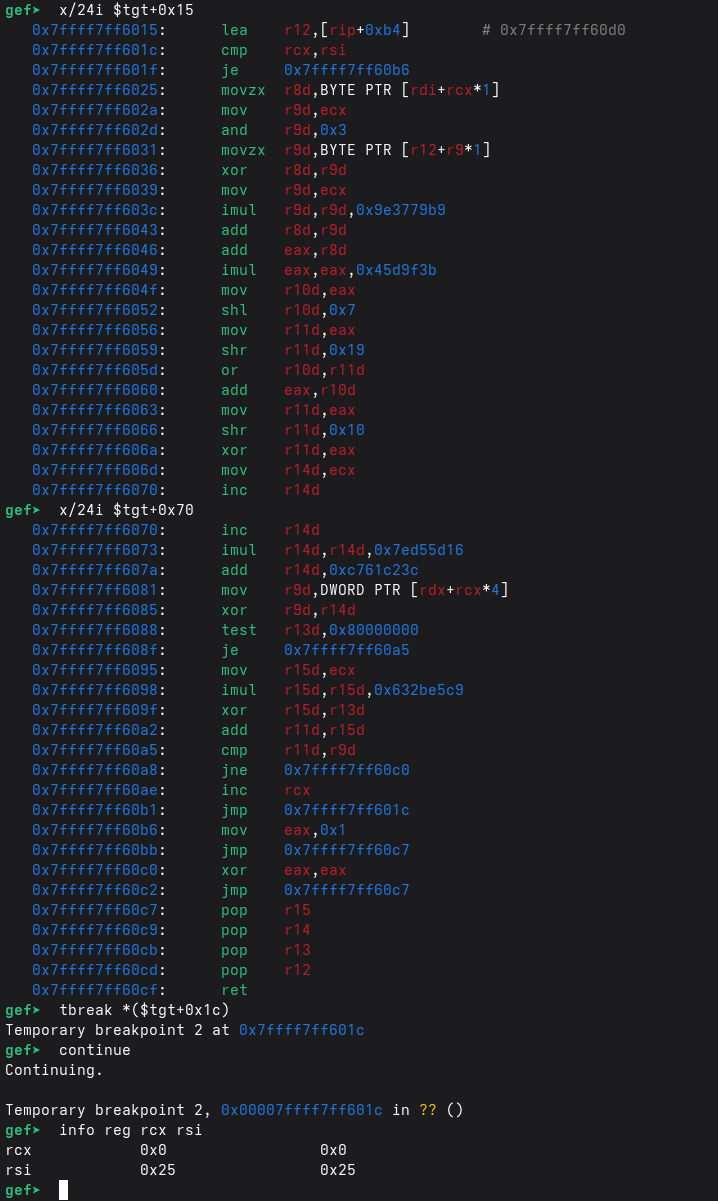

Into runtime code#

a.k.a the hidden validator

Single-stepping (si) over the call *... moves RIP into an address like:0x00007ffff7ff6000 (cf. gef screenshot above)

That address range is suspicious:

- not inside the main binary mapping

- not a typical libc

.textregion - looks like a dedicated mapped page

This strongly suggests: the validator code is unpacked/constructed at runtime and executed directly.

The fastest way forward is to dump the page and analyze it.

Dumping runtime artifacts#

- We dump the validator page which is a typical size of

0x1000bytes:

dump binary memory validator.bin 0x7ffff7ff6000 0x7ffff7ff7000

- We dump the constant table used by the validator.

The table is addressed via (%rdx, %rcx, 4) = that’s an array of 32-bit words.

Length is 37 = 37 dwords = 148 bytes = 0x94

If table base is 0x21eda0, then end is:

0x21eda0 + 0x94 = 0x21ee34

dump binary memory table.bin 0x21eda0 0x21ee34

- We dump the 4-byte cycling XOR key (the “salt”)

Near the end of the validator, a short 4-byte region is used via (i & 3) indexing:

x/4bx 0x7ffff7ff60d0

Observed bytes:

42 19 66 99

Reading the validator logic#

The validator iterates over each byte of the input and maintains a 32-bit accumulator/state (eax).

The loop structure is explicit in the dumped validator page:

cmp rcx, rsi; je ...showsrsiis the loop bound (input length) andrcxis the byte index.movzx r8d, BYTE PTR [rdi+rcx]confirmsrdiis the input buffer.mov r9d, DWORD PTR [rdx+rcx*4]confirmsrdxis the base of auint32_ttable indexed byi(rcx), matching the(%rdx,%rcx,4)addressing used to justify dumping 37 dwords.and r9d, 0x3+movzx r9d, BYTE PTR [r12+r9]shows the 4-byte XOR key is selected via(i & 3)from a small byte array atr12(loaded bylea r12, [rip+0xb4]).

For each position i:

- Mix the input byte with a 4-byte repeating XOR key

- Add an index-dependent constant (

i * 0x9E3779B9) - Fold it into

eaxwith multiply/rotate-style avalanche - Derive a check value (

r11) fromeax - Mix a per-index constant (

r14) with a table entry - Compare computed vs expected; fail fast on mismatch

This is a classic “rolling hash with per-position targets”.

Why byte-by-byte#

At step i, the check is F(eax_i, b_i, i, table[i]) == 0, where eax_i is fully determined by bytes [0..i-1]. Therefore we can enumerate b_i ∈ [0..255] independently, then advance state.

So at iteration i, the check depends on:

- the previous state

eax(which depends on earlier bytes only) - the current candidate byte

b - constants (

table[i], XOR key, multipliers)

So for each position, brute-forcing b ∈ [0..255] is feasible:

- test each byte

- keep the one that satisfies the equality

- advance to the next index with the updated

eax

In many CTF validators, there is exactly one satisfying byte per index, producing a unique solution.

Reconstructed algorithm#

Constants:

K4 = [0x42, 0x19, 0x66, 0x99]EAX0 = 0x72616E64C1 = 0x9E3779B9C2 = 0x045D9F3BC3 = 0x7ED55D16C4 = 0xC761C23C

All arithmetic is modulo 2^32.

For index i and input byte b:

r8 = (b & 0xFF) ^ K4[i & 3]r8 = r8 + (i * C1)eax = eax + r8eax = eax * C2eax = eax + rol32(eax, 7)r11 = eax ^ (eax >> 16)r14 = (i + 1) * C3 + C4target = table[i] ^ r14- check:

r11 == target

If any index fails, the validator returns 0. If all 37 positions pass, it returns 1.

As you could think it depends on r13d but it works so I guess it’s ok.

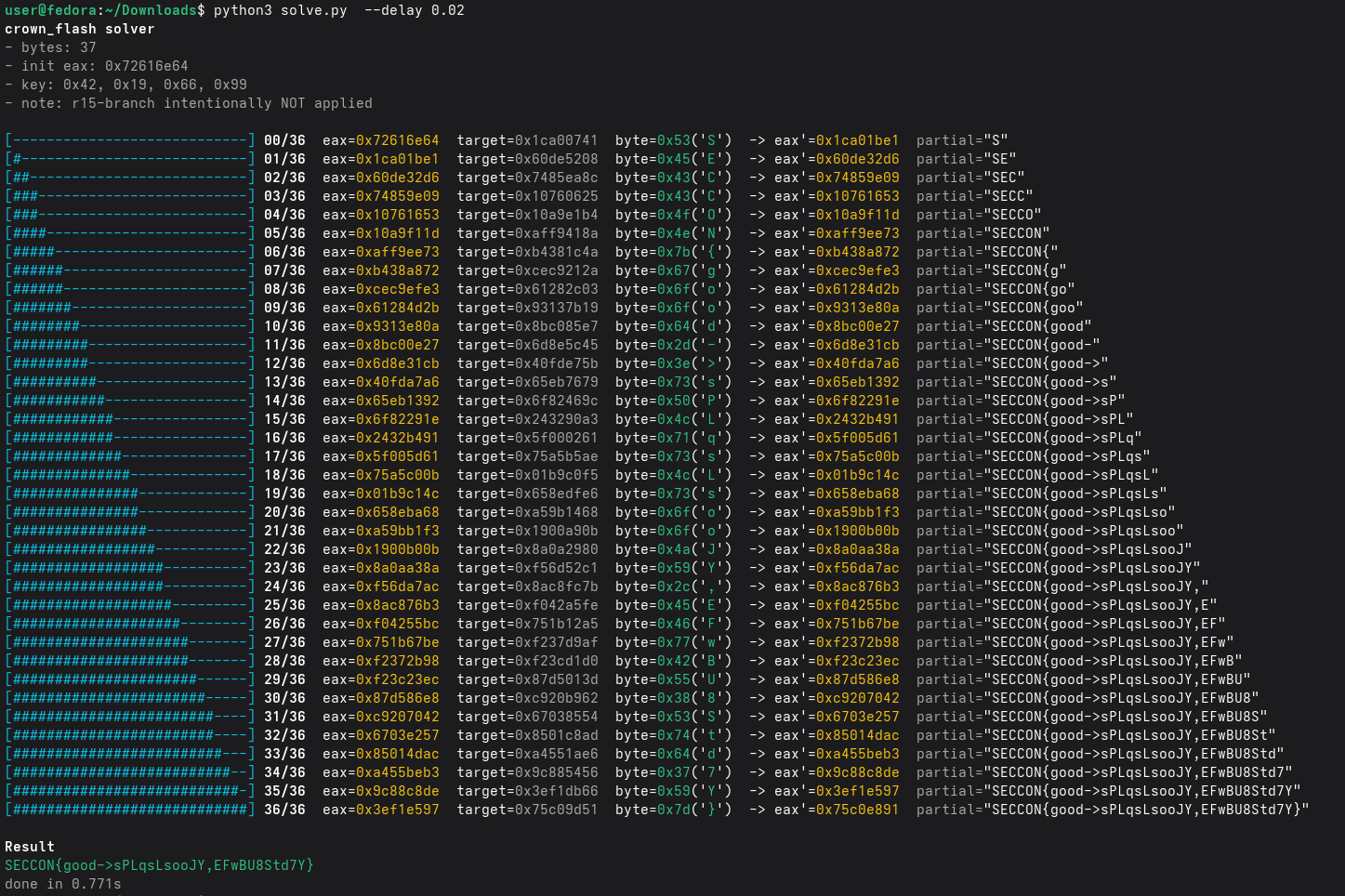

Python solver#

#!/usr/bin/env python3

"""

crown_flash (SECCON) - byte-by-byte stateful solver (pretty output)

- Replays the validator's per-byte update of EAX

- Inverts each step by brute-forcing the next input byte (0..255)

- Produces a readable trace suitable for screenshots

"""

from __future__ import annotations

import argparse

import string

import sys

import time

from typing import Tuple

# ---- Constants extracted from GDB ----

KEY = [0x42, 0x19, 0x66, 0x99] # bytes at 0x7ffff7ff60d0

TABLE = [

0x5A971813, 0xA5D22E60, 0x376433F2, 0xD2C130B1,

0x5125721E, 0x6F98B14A, 0x8B0F519C, 0x70C58BC6,

0x5DCA2401, 0x28A41E01, 0xB14C47C9, 0xD4EC4301,

0x78CA9B01, 0xD2E7AF09, 0x5A60701A, 0x9085033F,

0x6C8CF2D3, 0xC7C7F866, 0x308E6A2B, 0xD583D812,

0x8B797162, 0xB4B76B2B, 0xA68736B6, 0x5E0F2E8D,

0xA0FF2519, 0x594F9386, 0x52F9812B, 0x5480290B,

0xD7B19C6A, 0x23B7ABED, 0xEA18BE84, 0xC50EE1A8,

0xA5E30ABF, 0x3BED05CE, 0x82052868, 0xA3930232,

0x69F8AB3B,

]

MASK32 = 0xFFFFFFFF

C1 = 0x9E3779B9

C2 = 0x045D9F3B

C3 = 0x7ED55D16

C4 = 0xC761C23C

INIT_EAX = 0x72616E64 # from: mov $0x72616e64,%eax

# ---------------------------------------------------------------------------

def u32(x: int) -> int:

return x & MASK32

def rol32(x: int, r: int) -> int:

x = u32(x)

return u32((x << r) | (x >> (32 - r)))

def step(eax: int, i: int, b: int) -> Tuple[int, int]:

"""

Mirrors the validator's per-byte update.

- r8 = (byte ^ KEY[i&3]) + (i * C1)

- eax = (eax + r8) * C2

- eax = eax + rol(eax, 7)

- r11 = (eax >> 16) ^ eax

"""

r8 = (b ^ KEY[i & 3]) & 0xFF

r8 = u32(r8 + u32(i * C1))

eax2 = u32(eax + r8)

eax2 = u32(eax2 * C2)

eax2 = u32(eax2 + rol32(eax2, 7))

r11 = u32((eax2 >> 16) ^ eax2)

return eax2, r11

# ---- Pretty printing helpers ----

class Style:

def __init__(self, color: bool) -> None:

self.color = color and sys.stdout.isatty()

def _c(self, code: str, s: str) -> str:

if not self.color:

return s

return f"\x1b[{code}m{s}\x1b[0m"

def bold(self, s: str) -> str: return self._c("1", s)

def dim(self, s: str) -> str: return self._c("2", s)

def red(self, s: str) -> str: return self._c("31", s)

def green(self, s: str) -> str: return self._c("32", s)

def cyan(self, s: str) -> str: return self._c("36", s)

def yellow(self, s: str) -> str:return self._c("33", s)

def printable_byte(b: int) -> str:

ch = chr(b)

if ch in string.printable and ch not in "\r\x0b\x0c":

if ch == "\n":

return r"\n"

if ch == "\t":

return r"\t"

return ch

return "."

def progress_bar(i: int, total: int, width: int = 28) -> str:

done = int(width * (i / total))

return "[" + "#" * done + "-" * (width - done) + "]"

def solve(verbose: bool, color: bool, delay: float) -> bytes:

st = Style(color)

eax = INIT_EAX

out = bytearray()

n = len(TABLE)

if verbose:

print(st.bold("crown_flash solver"))

print(st.dim(f"- bytes: {n}"))

print(st.dim(f"- init eax: 0x{INIT_EAX:08x}"))

print(st.dim(f"- key: {', '.join(f'0x{x:02x}' for x in KEY)}"))

print(st.dim("- note: r15-branch intentionally NOT applied"))

print()

t0 = time.time()

for i in range(n):

# target = table[i] ^ (((i+1)*C3) + C4)

r14 = u32(u32((i + 1) * C3) + C4)

target = u32(TABLE[i] ^ r14)

found = None

next_eax = None

for b in range(256):

eax2, r11 = step(eax, i, b)

if r11 == target:

found = b

next_eax = eax2

break

if found is None or next_eax is None:

raise RuntimeError(f"No byte found at index {i} (eax=0x{eax:08x})")

out.append(found)

if verbose:

bar = progress_bar(i + 1, n)

ch = printable_byte(found)

partial = out.decode("ascii", errors="replace")

print(

f"{st.cyan(bar)} {st.bold(f'{i:02d}/{n-1:02d}')} "

f"eax={st.yellow(f'0x{eax:08x}')} "

f"target={st.dim(f'0x{target:08x}')} "

f"byte={st.green(f'0x{found:02x}')}('{st.green(ch)}') "

f"-> eax'={st.yellow(f'0x{next_eax:08x}')} "

f"{st.dim('partial=')}\"{partial}\""

)

if delay > 0:

time.sleep(delay)

eax = next_eax

dt = time.time() - t0

result = bytes(out)

if verbose:

print()

print(st.bold("Result"))

try:

s = result.decode("ascii")

print(st.green(s))

except UnicodeDecodeError:

print(st.green(repr(result)))

print(st.dim(f"done in {dt:.3f}s"))

return result

def main() -> None:

ap = argparse.ArgumentParser(description="crown_flash solver (pretty output)")

ap.add_argument("-q", "--quiet", action="store_true", help="only print the final flag")

ap.add_argument("--no-color", action="store_true", help="disable ANSI colors")

ap.add_argument("--delay", type=float, default=0.0, help="sleep N seconds between steps (for nicer screenshots/videos)")

args = ap.parse_args()

flag = solve(verbose=not args.quiet, color=not args.no_color, delay=args.delay)

if args.quiet:

try:

print(flag.decode("ascii"))

except UnicodeDecodeError:

print(flag)

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()

Sanity checks#

To be confident the reconstruction is correct we:

- Confirm the validator reads

table[i]as dword:- instruction pattern:

mov (%rdx,%rcx,4), %r9d

- instruction pattern:

- Confirm input length is fixed:

rsi == 0x25at the validator entry

- Confirm the XOR key is used with (i & 3):

- pattern:

and $0x3, regthenmovzbl (key + reg), ...

- pattern:

What I learnt#

- Syscall-first dynamic reversing is the fastest route when symbols are stripped and code is relocated.

- An indirect call into a “weird” region is a strong unpack/JIT indicator.

- Dumping a runtime validator + constants is often all that’s needed to solve.

- Rolling-state validators are frequently solvable incrementally (256 brute-force per byte) when each index has an independent target.

FLAG: SECCON{good->sPLqsLsooJY,EFwBU8Std7Y}